What is a Geopark?

The purpose of UNESCO’s Global Geopark initiative is to highlight and preserve outstanding locations around the planet that illustrate significant chapters or distinct events in Earth’s long history. Their purpose is to promote further geological research, heighten public outreach and literacy in geology and Earth science, showcase different cultural uses of landscapes and geological settings in the course of human history, and to develop ecologically sustainable geotourism for the benefit of local communities.

A working group was set up in mid-2021 to start the process of seeking UNESCO Global Park status for Georgian Bay; the National Committee in Ottawa recently designated the area as an ‘aspiring geopark’. This was the key first step in the process of making the case to UNESCO for full status in 2022, currently in preparation and discussion.

So why Georgian Bay?

Georgian Bay exceeds all the criteria for designation as a UNESCO Global Geopark and would be Canada’s largest (more than 15,000 km2). Its landscapes and culture are unique in Canada and helped shape a distinct national identity after 1867 as the young country learned to love its harsh uncompromising heartland; the Canadian Shield.

On the world stage, if Earth history is a like a book then the Georgian Bay is a major character in the story. Its highly deformed rocks, formed deep at the base of tectonic plates and now exposed at surface by erosion, inspired the Canadian father of plate tectonics, Jock Tuzo Wilson, and confirmed that continents drift with the opening and closing of oceans in a never-ending cycle. The Canadian Shield records key phases in the growth of the North American continent as a result of these cycles.

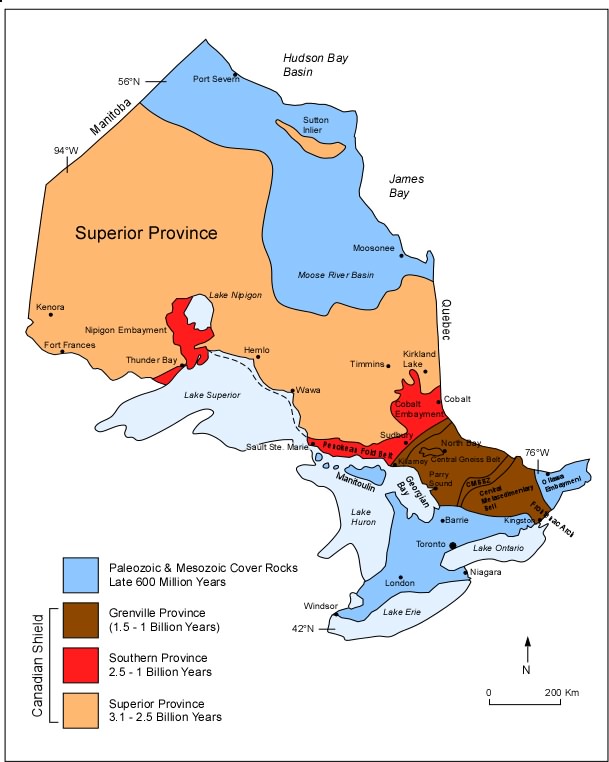

For the last 3 billion years, Georgian Bay has been a violent frontier, a collision zone between enormous tectonic plates. Both South America and Africa were once former neighbors locked together in the area that we now call Georgian Bay, imprisoned in giant supercontinents that broke apart leaving parts of these landmasses behind small crustal blocks known as 'terranes'. Each collision built giant mountains, now levelled by erosion and exposing their deeply eroded crystalline roots forming what we now call the Canadian Shield (Figure 1). This has afforded geologists unsurpassed details of the processes that occur at the base of the continental crust as it moves across the mantle below.

Figure 1- Georgian Bay in relation to the Canadian Shield in Ontario

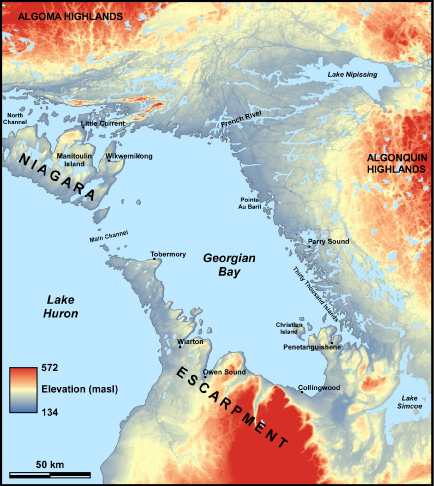

However, the story doesn’t stop there! More ‘recently’, beginning about 600 million years ago as North America broke away from its continental neighbors and later drifted across the equator, warm inland seas encroached across the Shield leaving a legacy of fossil-rich limestones and ancient tropical reefs. These make up some of the region’s most notable scenic features which can be seen today on the western side of the Bay along the limestone plains of the Bruce Peninsula and Niagara Escarpment on Manitoulin Island (Figures 2 and 3). Ancient earthquakes are also recorded in these rocks and provide clues to the origins of modern earthquakes in mid-continent today.

Figure 2- Characteristic coastline along the Bruce Peninsula where the Niagara Escarpment meets Georgian Bay

Figure 3- The view from the Niagara Escarpment on Manitoulin Island

The shaping of Georgian Bay and it environment

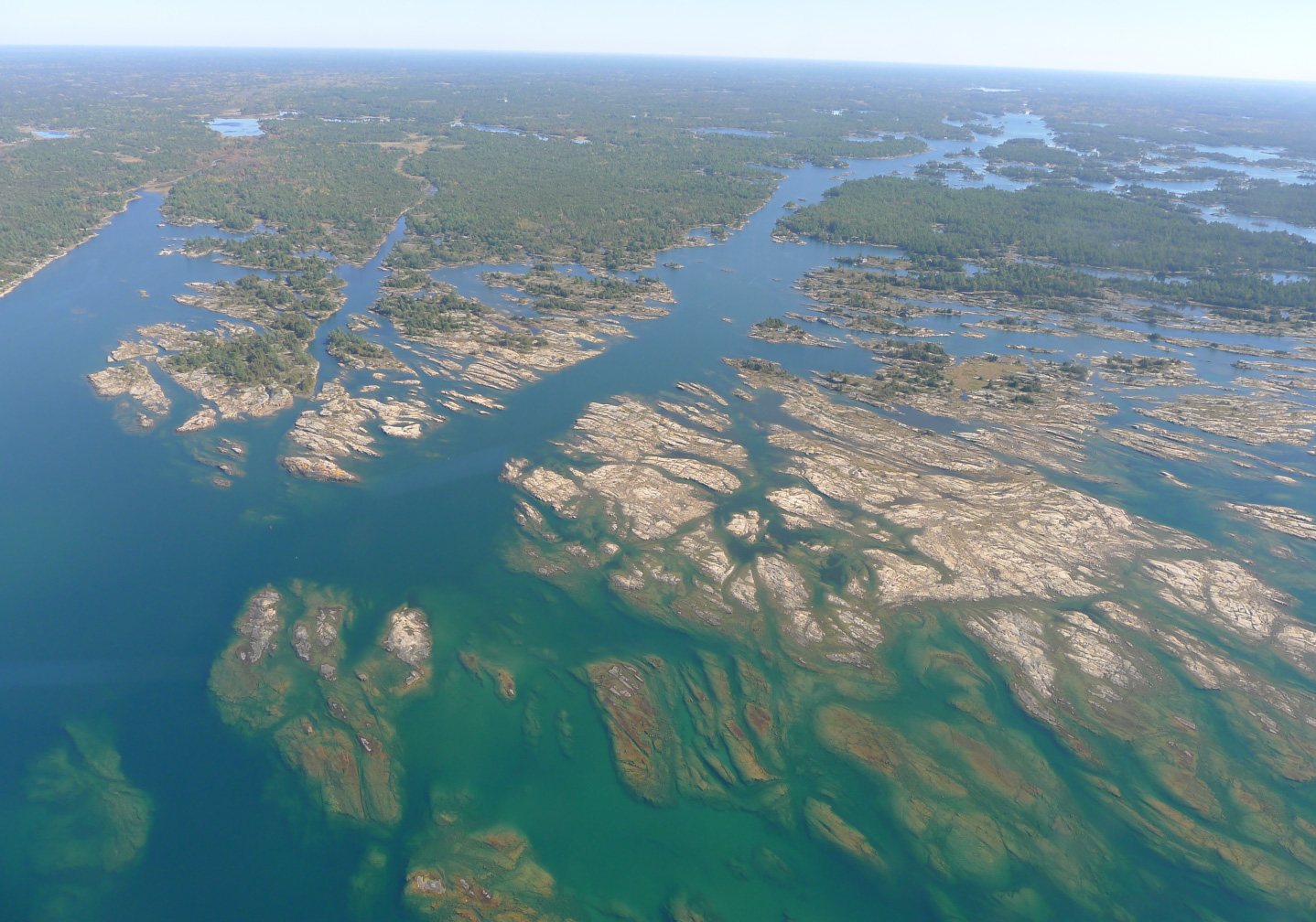

Although the Bay itself is an arm of Lake Huron it contains more than 5% of the planet’s freshwater. Like all the other Great Lake basins, the Bay is geologically recent in age, less than 2 million years old in fact. The basins were eroded into the Shield by giant ice sheets, like the kind seen in Antarctica today, flowing from kilometer-thick snowfields in Quebec-Labrador. Glacial scouring of the Shield produced more than 30,000 islands, the largest freshwater archipelago anywhere in the world. This archipelago is home to a unique North American ecosystem being composed of a mixture of northern boreal species with southern temperate species; what ecologists refer to as an ‘ecotone’ that collectively is more diverse than either north or south ecosystems independently.

Figure 4- Aerial view of the 30, 000 islands archipelago in Georgian Bay

Human history of Georgian Bay

The human history and cultures around the Bay are similarly the product of the ebb and flow of First Nations and Europeans, and accordingly are among the most diverse in Canada. Hardy Paleo-Indians first appeared in the area some 11,000 years ago just as glacier ice finally disappeared from the Bay. They had followed caribou herds along the shores of an enlarged and much deeper lake, geologists called Glacial Lake Algonquin, that was then infested with icebergs from the retreating ice sheet. Later, indigenous migratory Ojibwe-Ottawa hunter-gatherers on the Shield traded furs for maize with densely-populated settled Huron (Wendat) communities on the rich farmland to the south. Indigenous Ojibwe legends tell of the Great Drying of the Spirit Lake when much of the floor of the Bay was exposed as climate warmed, now known to have been about 7000 years ago. Wyandot legends speak of the god Kitchikewana guarding the Bay’s water, throwing clods of earth into its waters to form the 30,000 islands of its eastern shore. Early French explorers such as Samuel Champlain (1615-16) travelled through the area and overwintered, leaving detailed accounts of natural landscapes, wildlife, indigenous culture and customs, naming the body of water now known as Georgian Bay as ‘La Mer douce’; the sweetwater sea.

Figure 5- Georgian Bay relative to the surrounding topography, shaped by its geologic history, and notable communities along its shores

Later, Georgian Bay was the frontier between opposing American and English naval forces in the War of 1812, a stepping off point for Arctic explorers such as Franklin (1825), and was the first location of systematic geological mapping in Canada which was conducted along its shores by the newly formed Geological Survey of Canada (1842). After 1880, growing ports along the south shore of the Bay such as Midland, Collingwood and Owen Sound, offered a last chance for impoverished settlers seeking a new homeland after having crossed the Atlantic for transshipment across to the upper Great Lakes and on to the rich farmlands of western Canada (Figure 5). The starkness of the Bay’s rugged eastern shoreline conditioned early Canadians’ perspectives on the economic use of the Shield who often endured great hardships in the process of ‘farming rock’ having been attracted by colonization roads that snaked up onto the Shield and the prospect of free land after 1865.

Read more about this in the Road of Broken Dreams: Victoria Road

As a result of its long cultural history the Bay is now a nexus of Metis, English and Indigenous cultures; a unique meeting place of different perspectives on the varied landscapes that surround the Bay and what it means to live on the edge of the rugged Shield.

Georgian Bay moving forward

Today, the region is moving away from a dependence on natural resources, primarily fishing and lumber, to tourism. The region welcomes millions of domestic and international visitors each year from Canada’s largest city (and airport) just 2 hours to the south drawn in to experience the Bay’s unique landscapes, waterscapes, and habitats. For many it is their first introduction to the Canadian Shield and the heart of the Canadian experience; it is a unique place that appropriately deserves designation as a UNESCO Global Geopark. This would not only accelerate understanding of the Bay’s world class geologic record and its potential for further understanding the planet’s long history, but also emphasize the need for protection and conservation of its landscapes, waters and ecology, while offering new opportunities for environmentally sustainable economic activity and geotourism.

Want to learn more about what Georgian Bay has to offer?

Stay tuned for future posts covering geologic sites around Georgian Bay that can be enjoyed for their scenic features and geologic significance!

Also feel free to check out the wealth of sites that you can find on the planetrocks map surrounding Georgian Bay for locations to visit on your next trip to area.