Beds and Joints

The grey stripes mark planes of weakness where groundwater travels more freely, usually along either joints (cracks) or beds of more porous sediment like sandstone. Groundwater has the effect or 'reducing' the iron in the rocks, changing the colour from red to greyish green.

Clastic Wedge

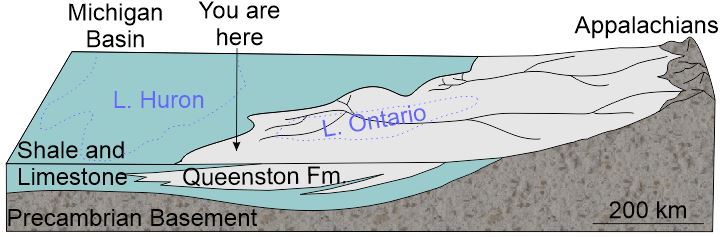

About 440 million years ago, a great mountain range called the Taconic Mountains was growing to the east. Sediment was shed away from the mountains into a "clastic wedge", to be deposited on an muddy coastal plain. These deposits are the "Queenstone Shale", which you see before you.

Introduction

The Cheltenham Badlands are beautiful deep gullies eroded into brightly coloured Queenston Shale. All vegetation and soil has been stripped by erosion such that the area resembles the classic badland region of southern Alberta. The term badland is in reference to the ease in which cattle would break their legs walking on such terrain, ironically the badlands were caused by overgrazing of livestock.

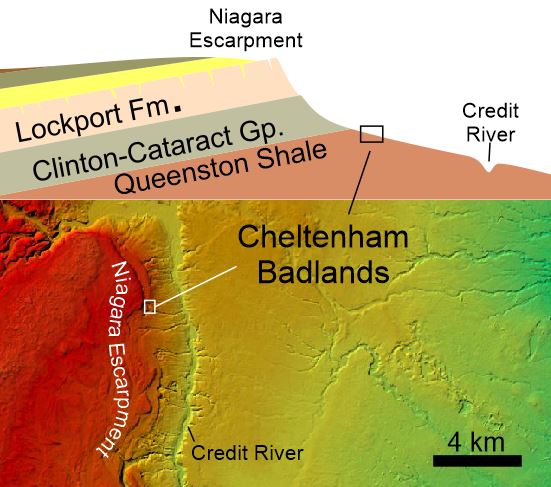

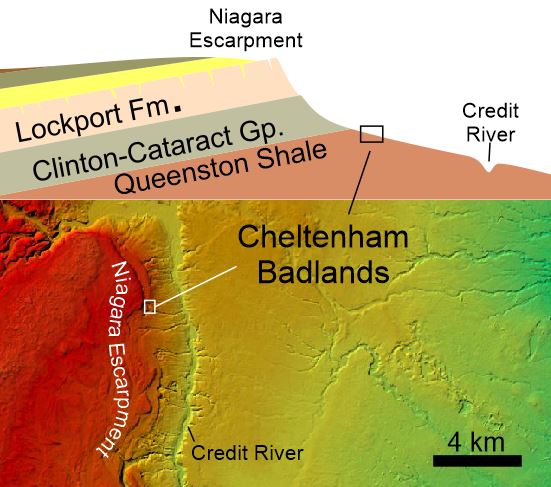

The Queenston Shale

The Queenston Shale, shown here in red, is the soft rock underneath the hard cap-rock of the Niagara Escarpment. It can be traced across southern Ontario.

Agricultural Malpractice

Stands of Apple and Hawthorne thickets can be found around the area and are related to the clearage of the landscape for cattle grazing in the early 1900's. Apple and Hawthorne thickets are indicative of cattle grazing.

Chinguacousy Badlands

Cheltenham Badlands is sometimes referred to as the Chinquacousy Badlands, referring to the "land of young pines".

A Chemical Breakdown

Every time it rains, the badlands are resurfaced. The shale is made of illite, chlorite, and kaolinite clay minerals, each of which shrink and swell different amounts when wet, causing the breakup of the rock into progressively smaller shards. Over repeated wetting and drying cycles, the suface becomes more compacted causing rain to runs off through the deep gullies.

Topography

This site is on a gentle slope of the Niagara Escarpment where underlain by the soft Queenston Shale. The whole slope is deeply gullied by channels feeding into the Credit River.

A Thin Glacial Veneer

Rare crystalline boulders from the Canadian Shield are the only hints of glacial activity having once scoured the landscape.

In the Red

The red color is due to the oxidation of iron in the shale. This may have happened fairly close to the time of deposition since these are paralic shales, meaning that they were deposited in shallow water where they were exposed to oxygen.